There have been 23 seasons of Gonzaga Basketball since the start of the 1998-99 season when they made their first Elite Eight. They have finished top 10 in adjusted offensive efficiency in 12 of those 23 seasons. Over 50 percent of Gonzaga teams the last 23 years have been elite offensively. For some reference, in that same 23-year span, Kansas has finished top 10 just nine times. North Carolina 10 times. Kentucky seven times. Arizona nine times. UCLA three times. Villanova five times. I didn’t go back and check every single team in college basketball, but the only “Blue Blood” type program I could find who finished top 10 more times than Gonzaga over the last 23 years is Duke. They’ve done it 18 times. They’ve finished outside the top 20 just once, which is absolutely insane.

All of that is to say, what Gonzaga has done offensively since 1999 is pretty unheard of. I’ve been paying close attention to the X’s and O’s of their offense the last couple of seasons, but I’ve never really gone back and studied old school Gonzaga. So that’s what I did this summer. I watched parts of close to 50 different games between 1999 and 2015. The reason I stopped at 2015 is because others have already done a lot of work on the seasons since then, and I will link you to those videos. Plus, the last six seasons have all basically built on what they started to perfect in that 2015 season.

For those who aren’t basketball nerds and don’t understand certain terms I throw out there, I will do my best to describe what you’re supposed to be looking at. Let’s get started shall we?

THE MOTION ERA

Up until the late 2000s, almost everything Gonzaga did was based on off-ball movement. They set very, very few ball screens. In fact, I counted the number of ball screens Gonzaga set in 22 different games throughout the years, and will post that toward the end of the article.

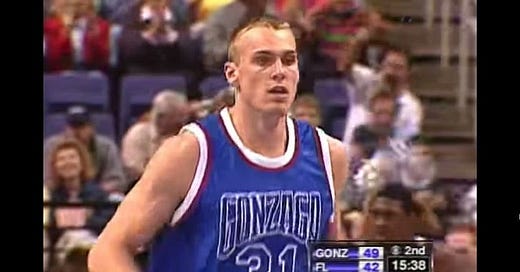

Gonzaga’s main offense during their 1999 Elite Eight run was Flex. It was one of the most popular motion offenses of the 90s and early 2000s. It feels like every single high school team in America ran it at some point during that era. For those who know the term, but not the action itself, the Flex offense is a continuous set of back screens (termed “flex” screens) followed by pin down screens. Here is Gonzaga running it against Stanford in the 1999 NCAA Tournament:

They would use several different entries to get into flex and several counters off of it, but at the end of the day, it was flex run relentlessly. One of the reasons Gonzaga was so successful in it is because their guards were incredible shooters coming off screens and they had forwards who would set incredibly difficult screens for defenders to get around. It’s extremely rare to find a group of guards square their feet and shoot the ball that well in tight spaces. Matt Santangelo, Quentin Hall, Richie Frahm, etc etc… All of these dudes were lights out coming off of pin down screens.

One of their favorite entries to get into flex was scissor entry. A scissor entry is when two guards cut off of the high post in a scissor like action. That high post receives the ball and those two guards will both get pin down screens. The initial goal is to get a three-point shot. As I mentioned above, watch how good Matt Santangelo was at shooting off screens in this first clip. And as you’ll see in the entire first half of this video, Gonzaga continues to run scissor action all the way through the 2021 season. But in the first several years of their accession, if this scissor entry did not result in a jump shot, they flowed directly into flex, which you’ll see in the second half of the video.

Their other most commonly used entry to get into flex was Carolina entry. Carolina entry is an action used in transition where the weak side guard comes up and sets a back screen for the trailing post. It was made famous by Dean Smith and perfected by Roy Williams. If you watch Gonzaga and North Carolina’s transition games over the last 15 years, you will find an outrageous number of similarities.

As you’ll see, Gonzaga used Carolina entry to get into their flex offense for many years. They also got some great lobs out of it. They used some form of Carolina action in transition for the better part of the last 20 years.

Now come the counters. Every defense in America understood what the flex offense was. Gonzaga, like most teams running it, would have counters to run if the defense was overplaying or cheating a certain way. One of those counters was a backdoor lob. Instead of receiving the pin down screen to come to the top of the key and reverse the ball, the big man would fake as if he were coming up, and then sprint to the rim for a lob dunk. Here is Gonzaga running the same play in the years 2000 and 2012. That’s right. The same counter 12 years apart and it still worked.

Their other counter is a double pin down for a shooter. Instead of receiving a back screen, which is what is supposed to happen in flex, the guard fakes as if he going to go to the rim and instead gets a double pin down screen to come to the top of the key for a three-pointer. They would sometimes run this as a set play, but for the most part, it’s just a read by the offensive player to see his defender cheating on that back screen and he makes them pay by getting caught up in a bunch of bodies.

You may be asking yourself: Wow, I’ve seen a lot of different Gonzaga teams in these videos already. How long did they actually run flex? Great question! They used it as a primary offense through the Dan Dickau years. They ran it as a secondary offense while Adam Morrison was there. And they pulled it out when they needed to all the way through the Rob Sacre era. In fact, they still ran it once in a long while when Kevin Pangos was in school. The latest time I could find them running flex was once during the Maui Invitational Championship against Duke in 2018. I kid you not, they tried to run flex for one possession in that game. It got blown up pretty fast and turned into nothing. But still, it was in the playbook, which is wild. I would not be shocked whatsoever if I look up and Chet Holmgren and Drew Timme are out there running the thing this coming season. Here is Gonzaga scoring off of flex all the way through Kelly Olynyk’s 2013 season.

I want to go through three of their most-used specials: plays they would call after timeouts or dead balls. The first one is an elbow set. The ball would get entered to either of the two big men around the elbow and he would fake a handoff to the point guard who entered it to him. As that is happening, the guard who started on the same side as the big man who caught the ball would sprint to the other side of the floor to receive a double pin down. Watch it in action:

You may notice in that video that Gonzaga ran this same thing on back-to-back plays (check the clock). That is something that Mark Few absolutely loves to do. He will run the exact same set until it finally gets stopped. He continues to do that all way to this day. You’ll see another example of it later in this article when we talk about ball screens.

This next set was a few years later when Dan Dickau and Blake Stepp were in school. It’s a horns stack set. This is one of the very few ball screen actions that Gonzaga used in the early 2000s. As you’ve seen so far, literally everything is off-ball screens and motion.

“Horns” is just what it sounds like, and looks like if you make horns with your hands. It’s two players around the elbow area flanking the point guard. In this version, there’s also a guard underneath each of them, making a stack. Dickau would choose a side and get a ball screen. Whichever side he chooses does “Spain” action, which is a back screen for the ball screener. The other side of the stack is a pin down screen for a shooter. This entire play allows Dickau to make a decision: Score off a ball screen, hit the roller, or find a shooter coming off the pin down. Here’s what it looks like:

The final special is a box set that turns into screen-the-screener action. It’s pretty self-explanatory. A guard sets an up-screen for a big and then receives a down screen from the opposite big. Here is Gonzaga running it in the 2001 NCAA Tournament.

This leads us into the next phase of Gonzaga’s evolution, which is playing through the post. When Mark Few took over for Dan Monson, one of his biggest initiatives was to play fast and play through their big men as much as possible. Basically every single Gonzaga roster the last 20 years, with the exception of a couple, have had multiple great big men. Because of this, Gonzaga became the king of the high-low game. Fans who have been around forever know how much of this they ran in the early-mid 2000s. It really hasn’t stopped much since then. This past season was a little bit of an exception because they were so perimeter oriented. Here is Gonzaga’s high-low action throughout the years, with some of these plays looking like an obsessive need to make the pass, even into traffic… and it still worked!

The other way big men got easy touches was in transition. You probably remember Drew Timme getting a ton of transition baskets this past season. Well, Gonzaga big guys have been sprinting the court and getting early post-ups for 20+ years now. The first two years of Mark Few’s tenure, Gonzaga finished fourth and third in two-point field goal percentage in all of America. They have finished in the top 20 in 15 of his seasons as head coach. They have had ZERO seasons finishing below 50 percent shooting inside the arc. ZERO!! One of the reasons for this is because they get so many easy looks at the basket in transition, just like this (some nasty dunks in here):

Eventually, Gonzaga moved away from running flex as their primary motion all of the time. Their early years motion still looked a lot like flex and had plenty of the same concepts, but was a lot more random and not as stringent. But again, all of it was based on movement and screens off the ball. It involved a lot of pass-and-screen away concepts, but it also introduced more flare screens, which Derek Raivio thrived off of.

In 2006, Gonzaga had an elite three-headed monster in Adam Morrison, Derek Raivio, and JP Batista. Their entire offense flowed through those three players. So much so, that they designed a play that literally only included them. And they ran it ALL THE TIME. But it worked because there were so many different options. It starts with Morrison passing to Raivio on the wing. Morrison receives a UCLA screen from Batista to go down to the post. Option one is to get Morrison a post isolation, where he was lethal. Option two, if that’s not there, is Batista setting a ball screen for Raivio. If the defense goes under the screen, Raivio shoots a three. If the defense is a step slow, he can drive to the rim. If all of that is covered, Batista, instead of rolling to the basket, sets a pin down screen for Morrison, who catches on the wing for a shot or a drive. There are three actions, multiple options, and three elite players making decisions based on how the defense plays it. Gonzaga would end up using this same UCLA set for multiple other players later on, mainly for Matt Bouldin.

After Morrison left, Gonzaga was in an interesting spot. They stopped having rosters full of multiple elite-level big men. The Josh Heytvelt Era turned a little bit more perimeter oriented. Part of that reason is because of Austin Daye. He was 6’11 but he didn’t like playing in the post; he wanted to be a pick-and-pop and wing slasher. So what Gonzaga did is implement a 4-around-1-motion offense. It was really the first time they used four perimeter players surrounding one post player over a prolonged period. The basis of the offense is pretty simple: Pass and cut to open up a new driving line for the next ball handler. All the while, the guy in the post is fighting for deep positioning, or he can step up and set a ball screen. If he does catch in the post, the spacing around him is better than if there were another forward inside, allowing him more room to operate. This 4-around-1 style is what we see much more of in modern day basketball.

Obviously, Gonzaga has had some elite individual playmakers throughout their 25-year run. On some of those teams without a lot of depth (2007, 2010, 2011, for example), Coach Few would just draw up floppy action and let those players make plays. Steven Gray was incredible at it his senior year. So was Matt Bouldin. And so was Kevin Pangos. They ran it more for Gray and Pangos than anyone else that I saw. Floppy action is very common in the NBA. You put your playmaker/shooter underneath the basket and he chooses a side. On one side, you’ve got a single pin down screen. On the other, it’s a double pin down. Set your defender up, choose a side, and go make a play. You’ll notice again in this video that Gonzaga runs the exact same play on back-to-back possessions for both Gray and Pangos. Run it until they stop it, baby!

BALL SCREEN EVOLUTION

We’re now deep into the 2000s. Up until this point, 90 percent of Gonzaga’s offense is predicated on movement, cuts, and screens off the ball. In the late 2000s, they start experimenting with more and more ball screens. The first new concept they enjoyed running was a “Spain” ball screen, which we mentioned earlier is a back screen for the ball screener. Remember how Gonzaga loves to run the same play until it gets stopped? The first half of this video is them absolutely obliterating North Carolina in the first half by running the same Spain action over and over and over.

The arrival of Kevin Pangos changed the entire program in so many ways. He helped usher in the new era of Gonzaga basketball, one that got the Zags back to the Elite Eight and laid the groundwork for their first Final Four. It wasn’t even what he did on the court, either. He played an enormous role in landing Przemek Karnowski. He also urged the coaching staff to take team chemistry to a new level, and it was in the 2010s when Gonzaga started putting a huge emphasis on individual growth, both on and off the court. Go listen to Mark Few talk about all this on Adam Morrison’s podcast if you haven’t already.

On the court, Gonzaga begins to change their whole philosophy. Instead of a motion offense where everything is based on off-ball movement, they start implementing a continuous ball-screen motion where the guards become the ultimate decision makers. You’ve heard the term “ball screen continuity” a million times the last decade surrounding Gonzaga basketball. The first time they tried running it was in the 2011-12 season. It was still new and raw and ended up having a lot of possessions look like this:

Like most new offenses, it takes time to perfect, both from the player’s side and the coach’s. Eventually, Gonzaga got there. They used it a bunch in the 2013 season with Kelly Olynyk and Elias Harris (first half of video) and it was generally pretty good, but it was truly perfected by 2015 (second half of video), Pangos’ senior year. You can see the fluidity of movement from everyone on the court by the time 2015 rolled around. Ball screen continuity is nearly impossible to guard once it gets to the third side of the court. Even the best defensive teams in the country can’t deal with it for 20 seconds. Eventually they break down and give up a basket. Gonzaga became disciplined enough to get to that third side of the court and they got easy basket after easy basket.

They also started adding in different types of ball screens. Not all ball screens are the same, for those of you keeping track at home. There are side ball screens, middle ball screens, open ball screens, etc etc etc. All of them are slightly different based on spacing. The one that became incredibly popular is their “zipper” series. It’s a middle ball screen off a zipper cut. You may remember the 2021 version of this in our full breakdown, but a zipper cut is a player cutting directly up the lane line, kind of like a zipper on a jacket. In this case, they cut up the lane line and receive a middle ball screen and play off of that. The reason zipper action is so effective, especially paired with screens, is because it forces the defense to trail the entire play. Their only real hope is to jump the passing lane for a steal; otherwise, they’ll be relying on team defense behind them once the offensive player catches the ball. The other thing this particular play does is sets up deep post position. Here is Gonzaga’s zipper series from the 2015 season:

Lucky for me, a lot of what has happened since 2015 has already been covered by other folks, so I don’t need to create my own videos. But the gist is this: Gonzaga has continued to build on that 2015 season. I would argue that 2015 team is the second best offense in school history, or at least right up there with 2019, behind the 2021 squad. They had the perfect blend of talent and high-IQ players where they could implement anything they wanted and the players would run it. All they’ve done since then is add more and more wrinkles to their ball screens and adjust for new personnel.

For example, in 2016, they ran more “horns” action than in any season in Gonzaga history because their best two players were Kyle Wiltjer and Domantas Sabonis. So why not include those two players in the majority of your actions?

The entire 2017 Gonzaga playbook is on YouTube if you would like to spend an hour of your time looking at it. It’s a lot of the same concepts that you’ve already seen, but it does a great job showing all the different types of ball screens Gonzaga used that season, both in transition and in the half court as they continued to add more and more.

Jordan Sperber, one of the best follows for X’s and O’s content, had a fantastic breakdown of the 2019 Bulldogs. By 2019, they started adding more movement on their ball screens – meaning the guy receiving the ball screen would already be on the move when catching the ball as opposed to just standing there waiting for a big man to come set him a screen.

And then of course, there’s 2021. And you can read that breakdown in its entirety by clicking here.

As I mentioned at the start of this, I kept track of Gonzaga’s ball screens throughout 22 different games from 1999-2021. And if you paid attention through this whole thing, you saw that Gonzaga started going more and more ball screen heavy in the late 2000s and then exploded in the 2010s. Here are the number of ball screens in those 22 games I watched:

1999 vs Stanford – 11

1999 vs Florida – 6 (mostly zone/press)

2000 vs Louisville – 5 (all switches/aggressive denials)

2000 vs St. John’s – 9 (zone/press)

2001 vs Virginia – 9

2001 vs Indiana State – 6

2002 vs St. Joe’s – 13

2003 vs Arizona – 20 (2OT)

2004 vs Tulsa – 10

2004 vs Santa Clara – 6

2006 vs Michigan State – 17 (3OT)

2006 vs Stanford – 8

2007 vs North Carolina – 30

2007 vs Washington – 21

2009 vs Tennessee – 30

2009 vs Western Kentucky – 26

2012 vs Arizona – 56

2013 vs Oklahoma - 45

2015 vs Arizona – 58

2019 vs Duke – 43

2020 vs BYU – 44

2021 vs Virginia – 59

Gonzaga won six NCAA Tournament games from 1999-2001 by setting a COMBINED 46 ball screens! They set 46 ball screens on a daily basis today. It’s wild to see how the game has changed and how Gonzaga’s offense has changed throughout the years. But the one thing that has never wavered is how good the Zags are running that offense. Doesn’t matter if it’s flex, or 4-around-1 motion, or ball screen continuity, Gonzaga figures out a way to thrive. And it’s thanks in large part to Mark Few and his long line of fantastic assistant coaches over the years.

There is SO MUCH that I missed. It’s literally impossible to break down 25 years worth of offense and get everything. But I tried to highlight the main stuff and tie it all together in a cohesive way. I hope you learned from it and enjoyed it. Even if you aren’t a huge X’s and O’s person, I hope it was at least entertaining watching some old Gonzaga players score some buckets.